In the three preceding articles of this series, I discussed the problems with the RPI this year and an alternative way for the Committee to make its 19 at large selections for the NCAA Tournament without using the RPI. The alternative goes through the following steps:

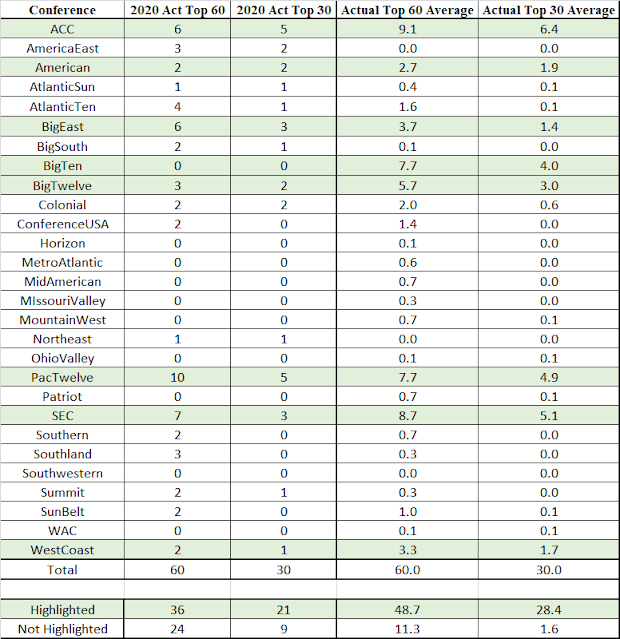

Allocates the 16 seed positions -- Tier 1 -- to conferences based on the average numbers of seeds they have had over the years since 2013 (the year of completion of the most recent major conference realignment).

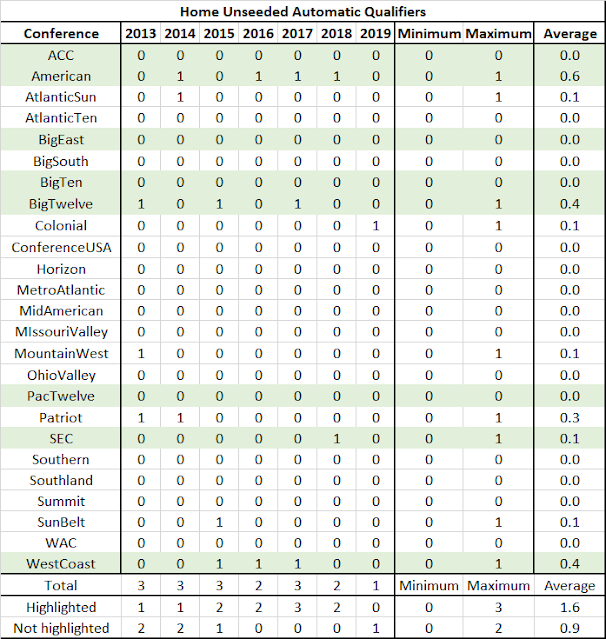

For the next 16 positions -- Tier 2 -- allocates them to conferences based on the average number of first round home games their unseeded teams have had over the years since 2013. (This results in more teams in Tiers 1 and 2 combined than will be needed to fill the 19 at large positions, even after taking Tier 1 and 2 automatic qualifiers into consideration.)

Creates a third group -- Tier 3 -- allocated to conferences to bring them up to the maximum number of teams they have had either seeded or unseeded but with first round home games over the years since 2013 -- as distinguished from the average number of teams.

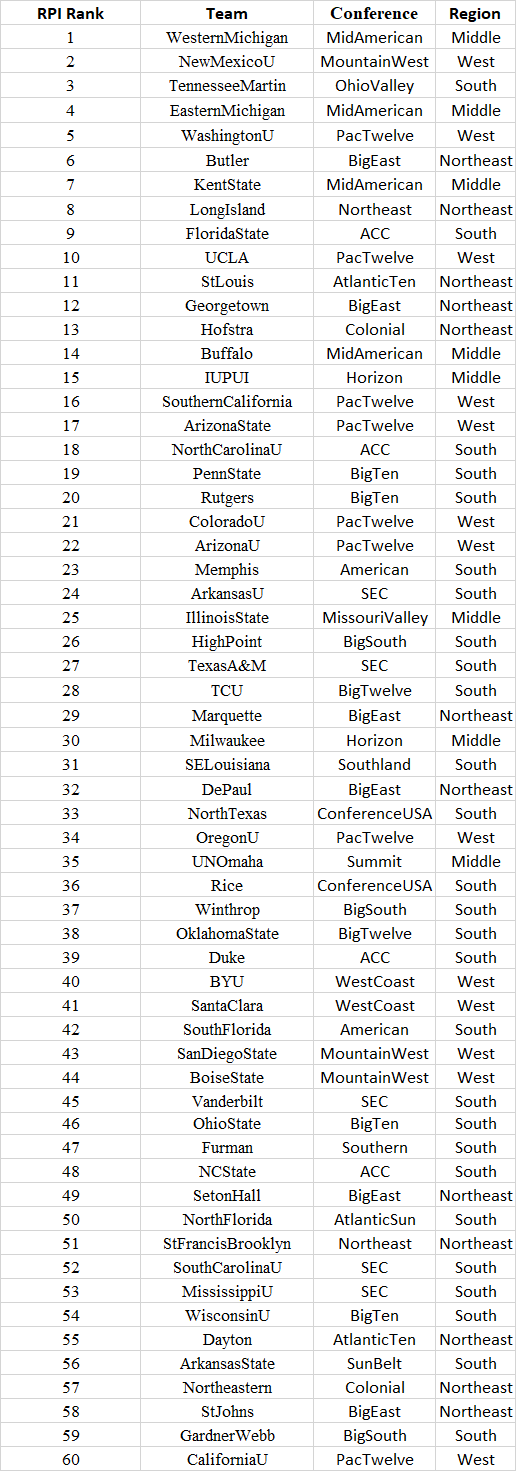

With the three tiers in place with their assigned conference slots, the next step is to do an initial fill of the slots with teams from the conferences. For each conference, the basis for initially filling the slots is team actual in-conference results during the current season. To do this initial fill, I assign each team a rank in its conference, based on where it finished in its conference regular season and where it finished in its conference tournament, with those two finishing positions weighted 50-50. If the conference does not have a tournament, then I assign the team the rank it had in its conference regular-season competition. Due to there being so many canceled games this season, I do the conference regular season rankings based on points per game. Once I have the assigned ranks of teams within their conferences, I then fill the conference tier slots starting with Tier 1, then Tier 2, then Tier 3.

I then look to see if any Tier 3 teams should trade places with any Tier 2 teams. Any replacement must be based exclusively on team results this season. After completing that step, I look to see if any Tier 2 teams should trade places with any Tier 1 teams, again based exclusively on team results this season.

When I have finalized Tiers 1 and 2, then the Tier 1 teams will be the 16 seeded teams. I count the number of Tier 1 teams that are not automatic qualifers and subract that number from 19 to tell me the number of automatic qualifiers that will come from Tier 2. Most likely, this will be 3 fewer than the number of Tier 2 teams that are not themselves automatic qualifiers. This means I will have to eliminate 3 of the Tier 2 teams. This elimination must be based exclusively on team results this season.

When I am done, I have selected 19 at large teams and they, together with the 29 automatic qualifiers, will make up the tournament field.

This process, applied to the actual results of games played through Sunday, March 28, combined with simulated results for all games not yet played including simulated conference tournaments, produces the following initial tiers of teams. As future actual results replace simulated results, the teams in the tiers will change. (The simulated results are right roughly two-thirds of the time.) Thus it is best to view the current three tiers as illustrating an historically appropriate distribution of slots among conferences, rather than focusing on the particular teams currently in those slots. In addition, since these are only the initial tiers, they would be subject to the review and potential trading of teams between tiers process I have described above. The yellow highlighted teams are actual or simulated automatic qualifiers.

I will update this table weekly over the closing weeks of the season.