This week’s reports use actual results of games played through Sunday, October 31. They are:

1. Actual current RPI ratings and ranks, showing which teams are in the current ranges for potential seeds and at large selections;

2. Simulated RPI ratings and ranks based on the actual results of games played and simulated results of games not yet played. The simulated results are based on opponents’ actual current RPI ratings. This report includes simulated NCAA Tournament at large selections and seeds based on the simple system described here.

3. Simulated NCAA Tournament bracket based on the simulated RPI ratings and ranks, using the more complex system described here.

For the tables below, you may need to scroll to the right to see the entire table.

1. Actual current RPI ratings and ranks, showing which teams are in the current ranges for seeds and at large selections:

Here is a link to an Excel workbook that shows current RPI and other information for all teams.

In addition, here is a table from the workbook. On the left, it shows which teams, based on past history, are in the current seed and at large selection ranges as of this stage of the season. It also includes the next group of teams, that appear to be close but out of the range for an at large selection. If you look at the At Large Bubble column, the highest ranked teams at the top of the list that are not color coded likely are assured of getting at large selections even if not conference automatic qualifiers, based on past history.

2. Simulated RPI ratings and ranks based on the actual results of games played and simulated results of games not yet played:

The simulated results of games not yet played are based on opponents’ actual current RPI ratings, as adjusted for home field advantage. This report includes simple-system simulated NCAA Tournament at large selections and seeds. [NOTE: I have more confidence in the more complex system simulated Tournament selections and seeds described in part 3 below.]

Here is a link to an Excel workbook that shows the information for all teams.

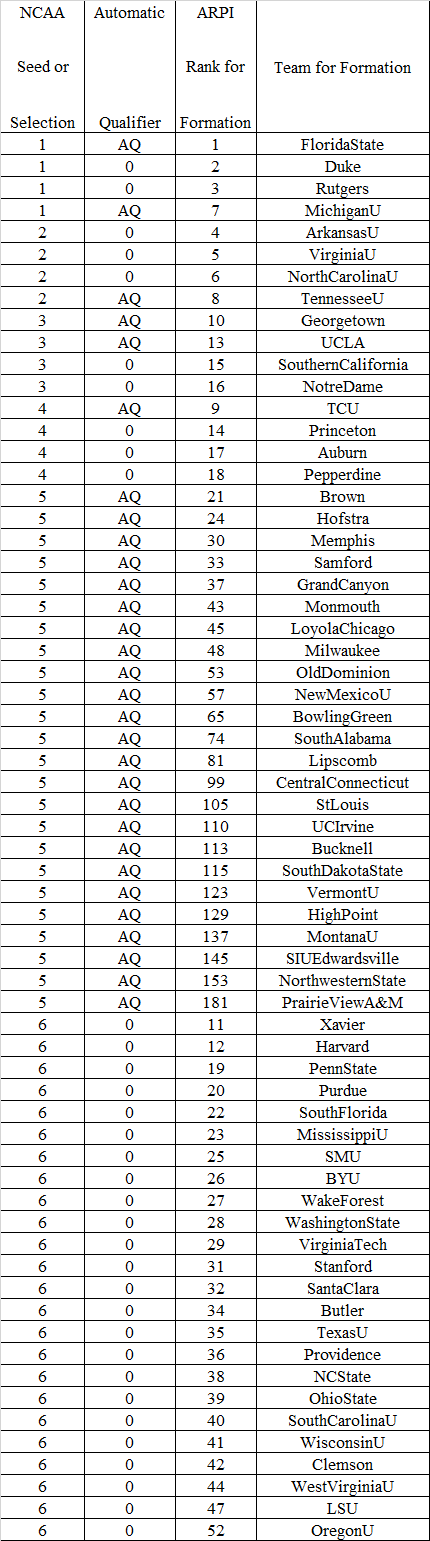

In addition, below is a table from the workbook that shows simulated simple-system NCAA Tournament at large selections and seeds.

I have put the table in RPI rank order this week for a particular reason. The table includes (1) the Top 57 RPI teams, since all at large selections since 2007 have come from the Top 57, plus (2) the Automatic Qualifiers. The simple system selects unseeded Automatic Qualifiers based on a formula that combines team RPI ranks and their ranks based on their good results against Top 50 opponents, with those two factors weighted equally. The Top 50 results ranks are based on a scoring system that is very highly skewed towards good results (wins or ties) against very highly ranked opponents. The simple system uses this dual factor because on average, over the years since 2007 (excluding 2020), the dual factor rank correctly matches all but 2 per year of the Committee unseeded at large selections.

In the At Large Selections column, the color coding shows the teams to which the simple system assigns at large selections. If a team is neither an Automatic Qualifier nor color coded in the At Large Selections column, it is a team that is among the Top 57 but that the simple system does not assign an at large selection. In the Seed columns, the color coding shows the teams that the system assigns seeds (with the seeds based on RPI ranks).

The table shows an interesting anomaly: The simple system assigns Harvard a #3 seed (as the #11 RPI team -- which has dropped to #12 as of November 2), but does not assign it an at large selection since it falls too far down on the dual factor list due to having no good Top 50 results (wins or ties). In response to this and because it will have educational value, here is a detailed analysis of Harvard’s record.

First, I looked to see whether the differences between Harvard’s RPI rating and its opponents’ ratings seemed appropriate based on game results. One of the things my system does is compute the RPI rating difference between opponents as adjusted for home field advantage. Then, based on that difference and historic data, it computes the likelihood of the higher rated team winning, tieing, and losing the game. If I then combine all of those likelihoods for a team’s schedule, I can tell what the ratings say the team’s win-tie-loss results should be for those games if the ratings for the teams are correct in relation to each other. I did this first for Harvard’s non-conference games and the RPI ratings say that Harvard’s record over the course of those games should have been 7 wins, 1 tie, and 0 losses (or possibly 7-0-1). In fact, its actual record was 7-1-0, exactly what it should have been if it and its opponents are rated correctly in relation to each other. I did this next for Harvard’s conference games, where the ratings say its record (so far) should be 5-0-1, whereas it actually is 4-0-2. What this suggests is that Harvard is rated appropriately in relation to the non-conference teams it played but is overrated in relation to its Ivy League partners Brown and Princeton.

Second, I looked at Harvard’s results against opponents it had in common with other current Top 60 teams. This showed the following, based on current RPI ranks as of November 2:

Harvard: win home v #60 St Johns who had a tie home v #30 Butler and a win home v #34 Providence

Harvard: win away v #106 Northeastern who had a win away v #25 Hofstra

Harvard: win home v #91 Kansas who had a win home v #45 West Virginia

Harvard: win home v #111 Penn who had a win home v #54 Rice

Harvard: loss home v #13 Brown who had a loss away v #25 Hofstra, a loss away v #15 Notre Dame, and a loss away v #34 Providence

Harvard: loss home v #18 Princeton, who had a tie away v #14 Georgetown and a loss home v #25 Hofstra

Harvard: win home v #128 Dartmouth who had a tie away v #14 Georgetown

Looking at the common opponent results as a whole, they suggest a Harvard rank in the vicinity of #25 Hofstra to #34 Providence, possibly closer to the Hofstra side of that range.

Putting these two detailed looks at Harvard together, it appears that Harvard’s current RPI rating and rank are too high. Realistically, it probably should be outside the range for a seed. On the other hand, it seems well inside the range for an at large selection.

The above analysis can give some insight into the process the Committee must go through.

Interestingly, my more complex system, as shown in the last table below, does not seed Harvard but gives it an at large selection. An at large selection certainly would be consistent with the history of Committee decisions, which always have given at large selections to teams with RPI ranks of #30 or better.

3. Simulated NCAA Tournament bracket based on the simulated RPI ratings and ranks, using the more complex system:

Finally, below is a table that shows the simulated more-complex-system NCAA Tournament at large selections and seeds.

Of the at large teams, the last teams in are Butler, Wisconsin, Houston, and West Virginia. The next teams in line are Oregon, Alabama, and Colorado.

1 = #1 seed, 2 = #2 seed, 3 = #3 seed, 4 = #4 seed, 5 = unseeded automatic qualifier, and 6 = unseeded at large selection.